Moments after the Jet Blach bicycle crashed, just as the team was lapped by Phi Kappa Psi on lap 150, and just as his confidence hit zero, Trent Hohenstreiter remembered the booming voice of Courtney Bishop, his legendary Little 500 coach.

Hohenstreiter thought back to the first speech Bishop delivered to him and two others before any of them decided to ride for Jet Blach.

In his deep and assertive voice, Bishop promised them that if one of the three joined Jet Blach, they would become Little 500 champions. If two decided to ride, Bishop said they will be part of the best Jet Blach team in history. And if all three decided to ride, they’d be the best team the Little 500 had ever seen. The speech was enough to sell Hohenstreiter on anything.

Now, with roughly 50 laps to go in the 2021 Little 500 race, Hohenstreiter mounted the bike and realized how close his team was to achieving the goal Bishop laid out. Hohenstreiter thought of the 11,000 miles he had logged over the past year. He remembered Bishop’s pre-race speech, driving home the idea that Jet Blach was the most prepared team in the race.

With constant motivation from Bishop, Hohenstreiter and his teammates mounted a comeback that joined Jet Blach with the lead pack, putting their sprinter Rob Krahulik in a position to win. Krahulik avoided another crash on lap 197 and edged the competition in an all-out sprint to the finish to win the 70th running of the men’s Little 500.

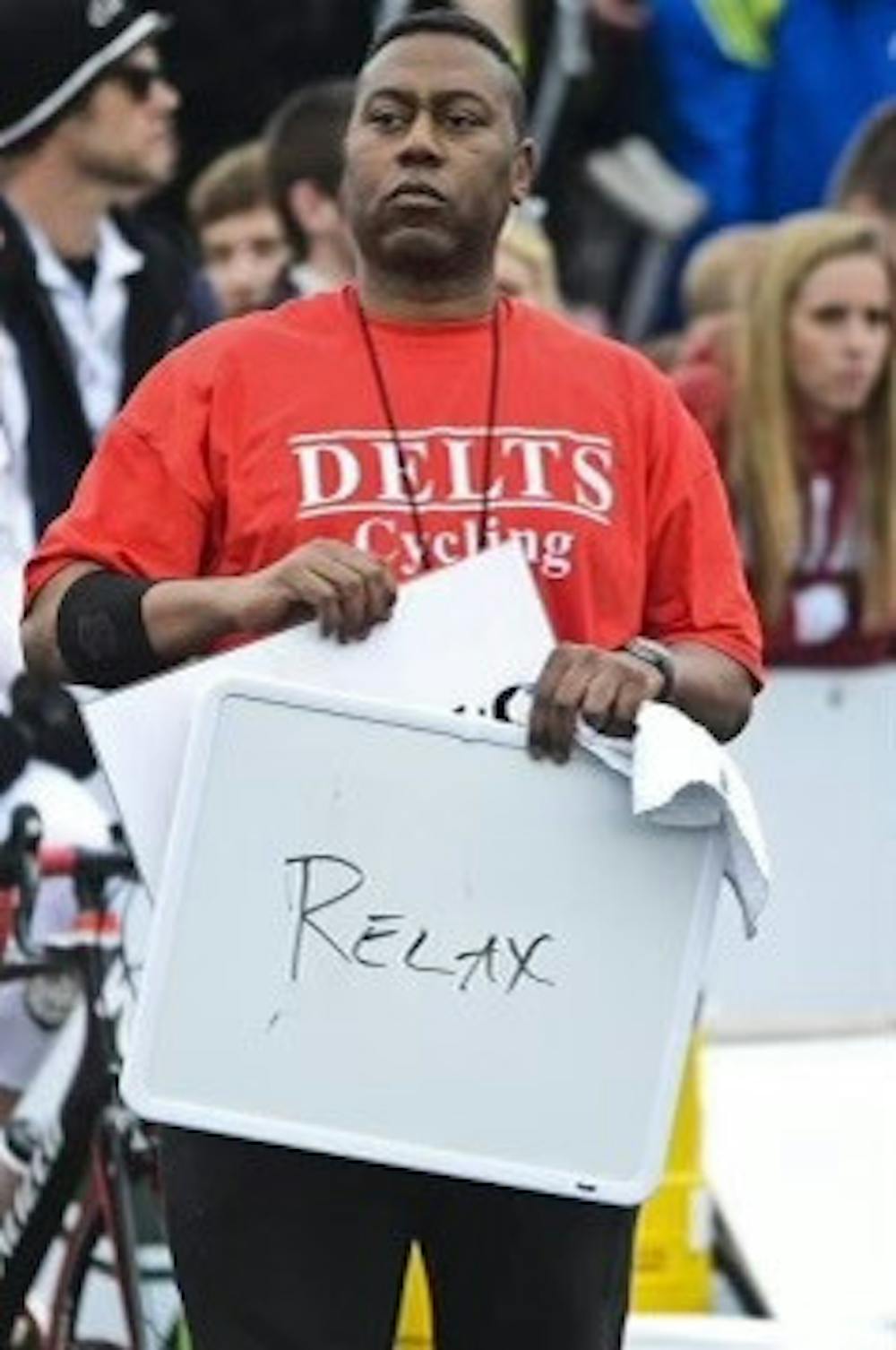

Bishop never doubted his team’s chances of winning the race in what he called his “Last Dance” as a cycling coach.

“You have got to tell them right to the bitter end, ‘We’re going to win this thing,’” Bishop said. “‘We’re going to find a way.’”

Bishop capped an epic Little 500 coaching career with his third first-place finish to go along with six second-place finishes and 15 top-five finishes as the coach of Team Major Taylor, Delta Tau Delta and Jet Blach. These accomplishments fall short to Cutters coach Jim Kirkham’s seven first-place finishes, but Bishop’s impact goes beyond the race track. For over 30 years, Bishop has reinvented the way the race is run and has broken racial barriers along the way.

“Everything [Bishop] says, and it doesn’t really matter what it is,” Hohenstreiter said, “you’re going to listen, and you buy in.”

* * *

Courtney Bishop was born in 1966 in Great Britain and moved to Brooklyn, with his single mother and two brothers when he was five years old.

“People today ask, ‘Hey, where’d the accent go?’” Bishop said. “And I tell them, ‘The last place on Earth you want to be a skinny Black kid with a British accent is probably Brooklyn.’”

Bishop’s family eventually relocated to Albany, New York, where he would attend high school. They were the only African American family in the neighborhood, but Bishop’s mother Dulcie A. Bishop was adamant about raising her sons in a nice neighborhood, even if it meant having fewer material possessions.

To pay for food, clothes and sports equipment, Bishop mowed lawns during the summer and started a paper route when he was 11 years old. But Bishop had to run his route: he didn’t own a bike and he wouldn’t finish in time if he walked.

So he draped one bag of newspapers over his right shoulder and another over his left and just ran. He did this for six years, and by the time Bishop was a senior at Albany High School, he was delivering 200 newspapers before school every day.

“I think that instilled in me just, ‘Hey, if you want something, you’re going to have to work and you’re going to have to get it, but you’re going to have to depend on yourself,’” Bishop said.

By high school, what Bishop wanted was track and field, which may be a product of his paper route runs. Bishop’s specialty was the one- and two-mile races. As he would step to the line before a race, Bishop would often look to the side and see his opponents laughing.

It was uncommon in 1980s Albany to see African Americans as distance runners, but Bishop used this disrespect to fuel his talent. He’d run 16 miles on some days in high school in pursuit of his dream.

“When I’m interested and I’m trying,” Bishop said, “I just feel like there’s nothing I can’t do.”

Bishop considered himself a “just OK” runner at Albany High School — his high school athletic claim to fame was becoming an all-state 800m and 4x400m runner. Bishop’s greatest value to one of the top high school track and field programs in New York was his guiding hand as a team captain.

“I was the guy that kept all of the guys together,” Bishop said.

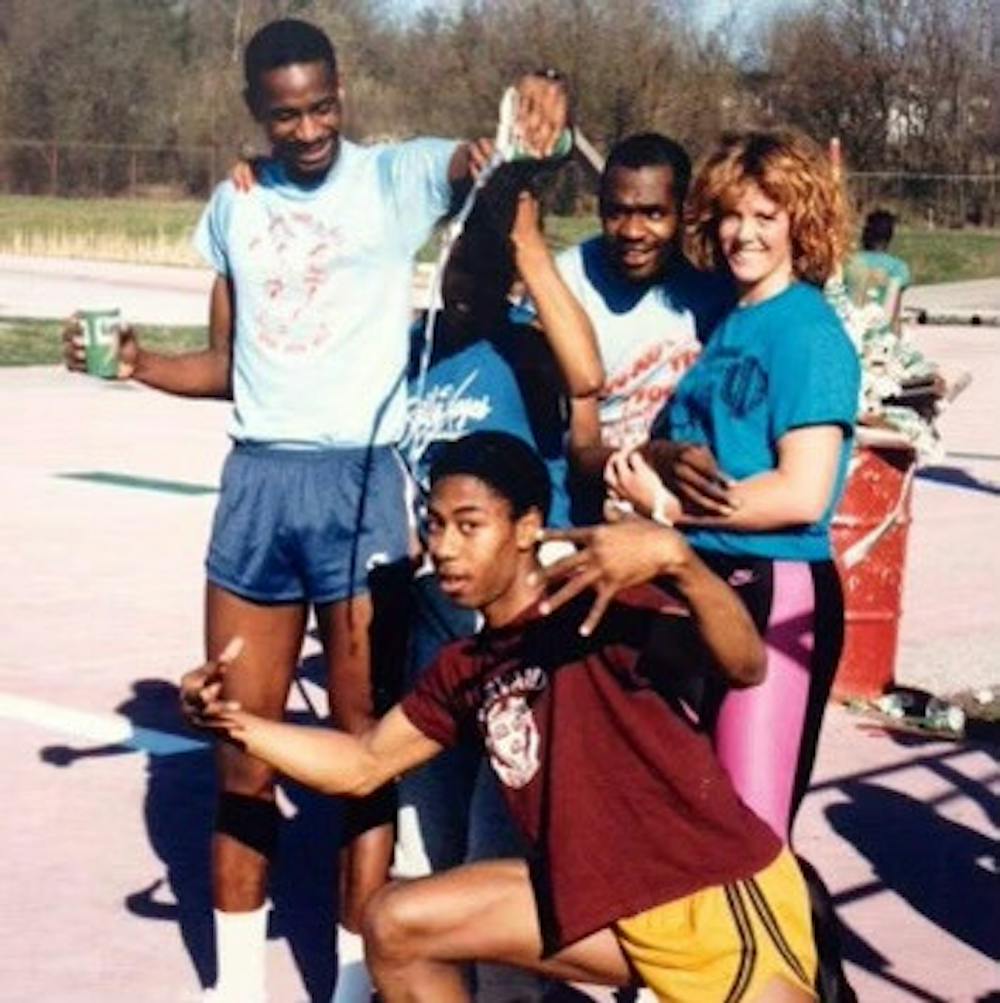

Bishop turned down scholarship offers from Eastern Michigan, Michigan State and Williams College to run under famed Indiana track and field coach Sam Bell. He was rarely chosen to race at Indiana’s top meets, but knew his experiences at Indiana didn’t happen with other schools.

“We’d think to ourselves, ‘We’d be the No. 1 guy at 95 percent of schools in the country. The guy,’” Bishop said.

At times, Bishop considered transferring, but Indiana was a powerhouse program at the time, and Bishop wanted to surround himself with the best. His roommate Mark Deady made the 1988 Olympics and what was considered Indiana’s “A-minus team” broke the American record for the 4x800m relay.

“Indiana in the ‘80s was Indiana,” Bishop said. “What I remember the most is what it took just to survive there every day.”

* * *

During Bishop’s time as a student at IU, the mornings of Little 500 races looked a bit different than they do today: Black students would head in one direction and white students in the other. The Black student picnic was held at the same time as the Little 500 race, but Bishop instead elected to attend the race in support of his fraternity and because of his interest in endurance sports.

Bishop often received puzzled looks of “What are you doing?” from strangers when he arrived at Bill Armstrong Stadium.

While Bishop is now regarded as one of the most impactful coaches in the race’s history, simply becoming involved with the race may have been his biggest obstacle. Bishop joined Acacia Fraternity in 1986, which has a rich cycling tradition that includes three first-place finishes and 23 top-five finishes in the Little 500.

But from the spring of his freshman year in 1986 to his last spring in Bloomington in 1990, Acacia finished in second place twice and third place once.

“Most of the time we’d come back like, ‘What happened?’” Bishop said. “We’d kill everyone in all of the series events, and we had just historic people riding for us. But we could never win.”

Bishop knew he had the athletic pedigree to help his fraternity brothers break through, and his infatuation with the Little 500 was enough for him to contemplate quitting track and field altogether.

Bishop finished out his collegiate career as a member of the Indiana track and field team and never had the experience of riding in the Little 500.

Throughout his years as a fan of the race, Bishop realized he was surrounded by white people watching other white people circle the cinder track. There were few Black fans in the stands, and there were zero Black teams.

“You couldn’t put up a bigger signal of what you are and are not allowed to do,” Bishop said. “So when I graduated, I wanted to change that.”

* * *

A lack of diversity at IU’s largest student event raised an important question for the Indiana University Student Foundation (IUSF): How do you attract Black fans to the race?

For Bishop, the answer was simple — you need a team.

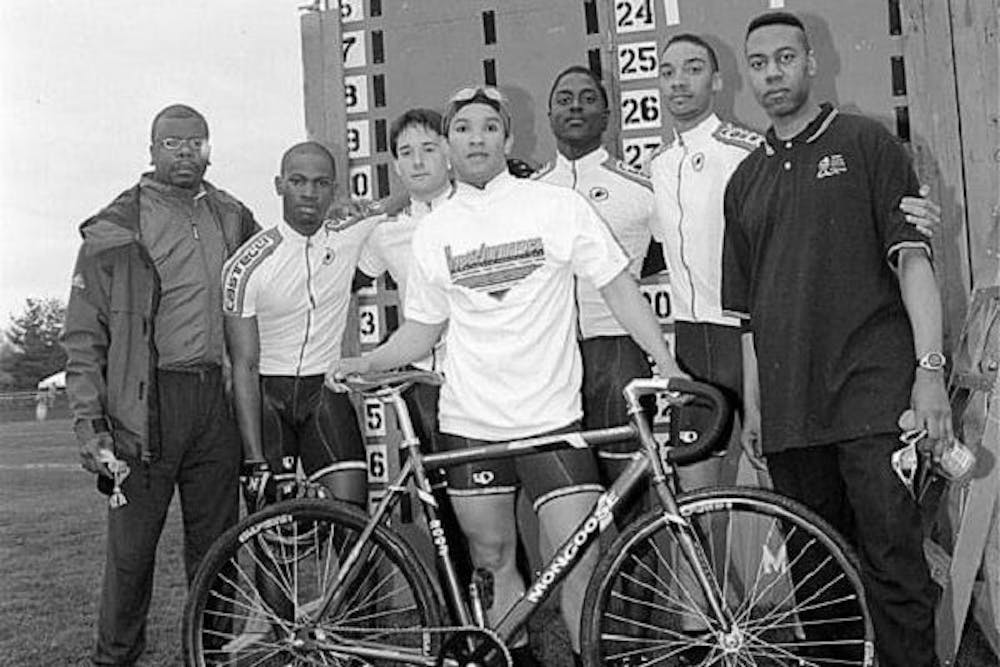

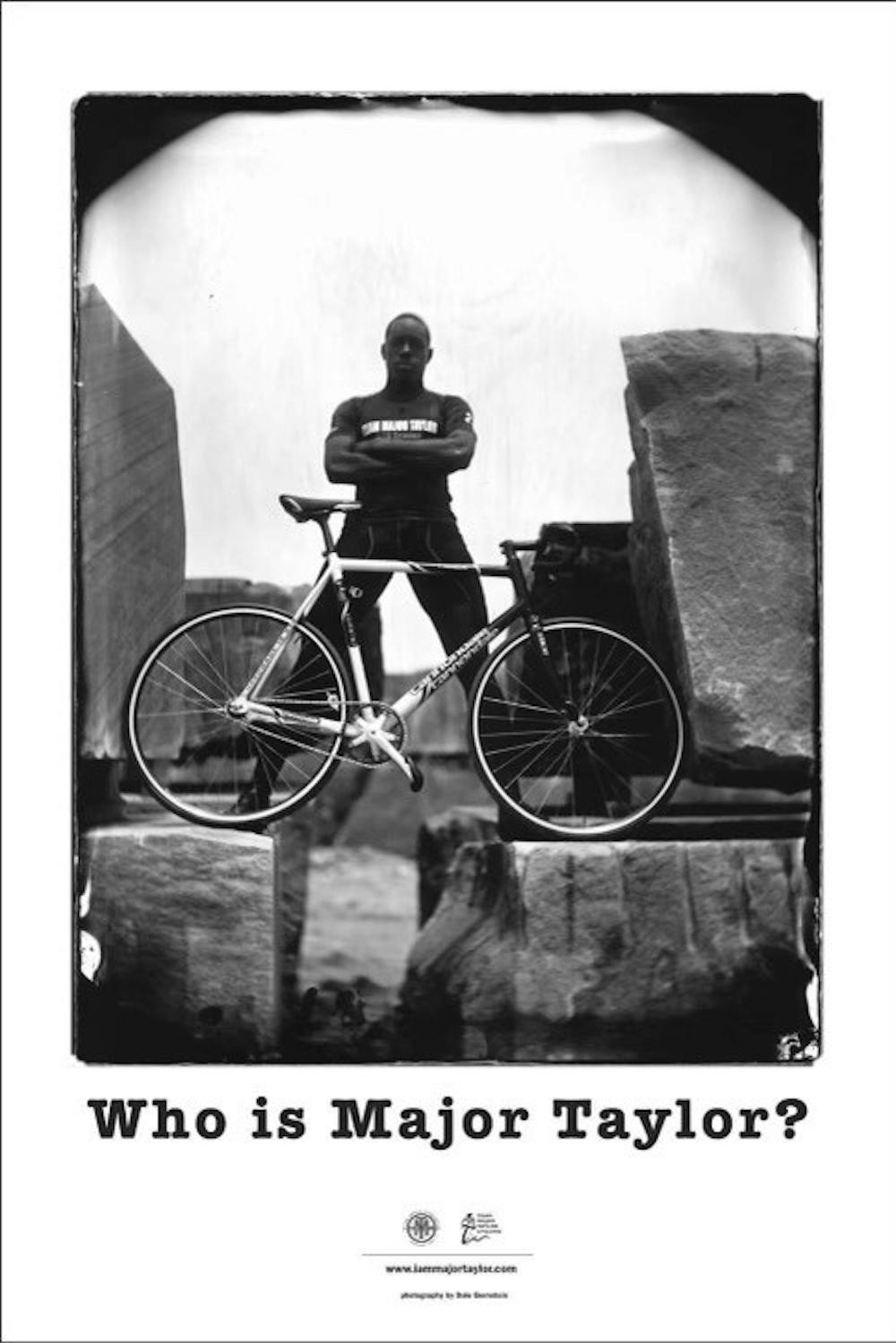

So in 1992, Bishop formed Team Major Taylor, an all-minority cycling named in honor of Marshall Walter “Major” Taylor, an African American cyclist who won the gold medal at the 1899 World Championships in Montreal.

Bishop’s first team wasn’t comprised of lifelong cyclists. Team Major Taylor finished last in its first race, was lapped 30 times and disbanded after one year. But in 2002, after a 10-year layoff, Bishop was asked by Charlie Helms, Indiana University’s chancellor at the time, and Frank Motley, an associate dean of the Maurer School of Law, to try again.

This new team was formed by what Bishop called “a giant phone tree.” Josh Weir was the only rider Bishop met in person, but Weir knew a rider in Los Angeles, who knew someone in Long Beach, who knew someone in Philadelphia, eventually stretching all the way to Trinidad and Tobago — where Bishop recruited Simeon Commissiong, who ended up being one of the great sprinters in Little 500 history.

The early years of Team Major Taylor were arduous, even for a leader like Bishop.

After all, he had no personal cycling experience. He didn’t own a bike until 2007 and sold it two months later. His desire to coach stemmed from his love for the Little 500 as a spectator and his goal to spread diversity in the race. So when nationally-ranked cyclists were told what to do by Bishop, who had no experience of his own, it sometimes resulted in conflict.

The main rider Bishop butted heads with was Kenny Burgess, who rode for Team Major Taylor in 2003 and 2004.

“[Bishop] is a strong-minded individual,” Burgess said. “Granted, he does listen, but at that point in time … he wanted to run things a certain way, and obviously we had different opinions.”

Burgess grew up in South Central Los Angeles and attended Crenshaw High School, which encompassed a neighborhood devastated by the 1992 Los Angeles riots. Burgess said growing up in this area gave him a different perspective on life. Burgess and his friend Rahsaan Bahati, who also rode for Team Major Taylor, lost friends to gang violence and grew up knowing to stay guarded and aware of their surroundings when walking down the street.

This implemented what Burgess called a bootstrap mentality, one that taught him to live with gumption.

In one of Bishop’s first meetings with Team Major Taylor, before the 2002 season, he decided to discuss post-graduation plans with the team. Bishop funded some of Team Major Taylor through his mortgage firm and hoped his business knowledge could help members of the team.

But early on in the meeting, Bishop sensed his message wasn’t connecting.

“Everyone (was) just kind of looking at each other,” Bishop said. “Kenny, specifically, was like, ‘Hey man, none of us are going to live til we’re 25. What are you talking about?’”

After losing friends to gang violence, discussing long-term goals and future aspirations wasn’t common in Burgess’ upbringing. Bishop said Burgess was essentially homeless in high school, so he wasn’t used to these types of conversations. Bahati introduced Burgess to a cycling coach when the two were in high school, and Burgess slept on the coach’s couch for a year and a half while training.

Bishop said Burgess and other riders’ difficult upbringings created another goal aside from bringing diversity to the race and forming a strong team. From that point on, Bishop made it a point to keep his riders in school and graduate as many as humanly possible.

“Even more than [riding in the Little 500],” Bishop said. “I am ecstatic about where all of them are in life.”

* * *

Simply creating Team Major Taylor was a challenge for Bishop, but the obstacles didn’t stop there. While other teams arrived at Bill Armstrong Stadium with their minds focused solely on the race, a police escort ensured Team Major Taylor’s safety on its way to the 2004 race.

Burgess said that rural Indiana has a history of racism towards African Americans, and their team felt that through racial slurs and booing.

“Those are things that I think about today,” Burgess said. “I’ve been called things at Indiana that I’ve never been called anywhere else in the world.”

Burgess and his teammates channeled this adversity on the track. There’s no doubt it affected Burgess mentally, but Bishop and Team Major Taylor banded together.

And as the team improved and became popular around campus, it gained a loyal following. In the 2004 race, Team Major Taylor held pole position. With Team Major Taylor positioned as the favorite to win the 2004 race, nearly 400 African American students filled a section of the bleachers at Bill Armstrong Stadium. Decked out in green, the fans were ready to witness history.

“That’s when it hit me like, ‘Wow, that’s why we did this,’” Bishop said.

For Burgess, so much of his life beforehand was based around competitive cycling. Usually, his mind was locked in on training, physical preparation and mental focus. But seeing growth in fan diversity made Burgess take a step back.

“When you have a certain sector of students that are basically representing students of color,” Burgess said, “at that point, it became a lot bigger than just winning the race.”

Bishop still considers Team Major Taylor’s performance in 2004 the best race ever run — even if it began with a slow start.

Team Major Taylor was trailing the pack, so Bishop left Simeon Commissiong, who was considered the best sprinter in the 2004 Little 500, on the bike for longer than usual. Commissiong made up a half lap in the amount of time that made the coach in the adjacent pit shout, “What the fuck?”

Team Major Taylor was back in contention, but Commissiong was gassed. For Bishop, it was time to change the game plan.

“I look at these three guys Julio [German], Steve [Ballenger] and Kenny [Burgess] and I’m like ‘[Commissiong] is not going on the bike til the end,’” Bishop said. “They’re looking at me like, ‘Dude, that’s not possible.’”

Bishop’s team was hanging tough, but German’s calf started cramping on lap 120. Commissiong began to plead his case to hop back on the bike.

“Nope. Sit down,” Bishop told him.

“What are we doing?” Burgess cried out.

“We’re going to go back and forth with you and Steve until the end of the race,” Bishop told Burgess.

“That’s not even possible,” Burgess replied.

In Bishop’s head, he didn’t even believe that what he was telling his team was possible. But at that point, they had no choice. Bishop had to make them believe.

After roughly 80 laps of alternating between two riders, Team Major Taylor was still in the lead pack. At that point, rumors around the pit were that Commissiong was hurt as the broadcast showed a trainer rubbing Commissiong’s hamstring. But with five laps remaining, Commissiong stood on the track and waited for an exchange. Bishop could see the immediate terror creep onto the opponents’ faces as they mouthed “Oh, shit.”

“You’ve gotta think Commissiong is licking his chops,” Jack Edwards, the Little 500 play-by-play broadcaster said with two laps to go. “This is the way that Team Major Taylor wanted it to unfold.”

But as Commissiong made the turn on the back stretch, his front tire tapped the bike next to him. Commissiong crashed to the ground, taking the Phi Gamma Delta and Briscoe teams with him. After riding a perfect race for more than 199 laps, it was over.

Bishop paced the sidelines with both hands covering his face. Commissiong unclipped his helmet buckle in disgust and stood next to his teammates bent over and staring at the ground. Burgess took his bike and left the stadium.

“I have won three times, but that was the one that got away,” Bishop said. “Even though we didn’t win, it was the best race ever run.”

* * *

This crushing defeat took a while for Bishop to process. After emotions cooled, Burgess remembers Bishop sitting Team Major Taylor down and giving a speech of positive reinforcement.

“These are things that make you stronger as a team,” was a phrase from Bishop that Burgess remembers.

While Team Major Taylor fell just short, Bishop’s goal of creating diversity in all aspects of the Little 500 remained an overwhelming success. An all-minority team was succeeding and spectators were more diverse than ever.

“This whole thing came from the point of people telling you, ‘You’ll never field a team. There aren’t five Black cyclists in America. How are you going to put a team together?’ Three years before that, to now, ‘Oh my God, we’re going to win this thing,’” Bishop said. “It was like going from the highest high to the absolute lowest low.”

Team Major Taylor’s appearance was different from any team in Little 500 history, and the way they raced was, too. Bishop created a race strategy from scratch that mimics the way a track and field runner would perform, not a cyclist.

As a student, Bishop watched the Little 500 from the perspective of a track athlete. To him, the Little 500 looked like a string of riders all going as hard as they could.

“I used to think to myself, ‘Man, if you were a runner you would never do that,’” Bishop said.

In Bishop’s experience as a distance runner, conserving as much energy as possible throughout the course of a race has always been a widespread philosophy. Runners want to be toward the front of the pack, but they don’t want to be forcing the issue or pushing the pace.

“When you get there and unveil it, it doesn’t look like anything anyone has ever seen before,” Bishop said. “It kind of looks ridiculous.”

But it wouldn’t be wise to laugh at Bishop’s innovative approach to the race. In Team Major Taylor’s first appearance in the Little 500 since reforming the team in 2002, they qualified third and finished ninth. The following year, the team qualified second and finished second.

That’s why Bishop deployed Commissiong late in 2004, and today, nearly every team mimics the strategy that Bishop taught his teams.

Jordan Bailey, the Little 500 race director from 2012 to 2016 and former Black Key Bulls rider, said Little 500 footage from the 1970s and 1980s shows riders pedaling as fast as possible the entire race. But by the 1990s and early 2000s, the nature of the race started to change and slow down, and Bishop’s philosophy was certainly a factor.

“I think there was a lot more strategy infused into it,” Bailey said. “Like, ‘We need to think about being strategic from a bike racing perspective’ versus trying to mimic the Indy 500 and just going full gas the whole time.”

As Bishop implemented this strategy, momentum began to build for Team Major Taylor. Bailey compared Bishop to a college basketball coach who recruits players that fit his system. Bailey always knew Bishop’s teams would enter the race with top-notch fitness, likely contending towards the later stages of the race.

While Bishop’s strategic mindset kept Team Major Taylor competitive nearly every year, Bailey said winning the Little 500 comes down to being able to inspire 18 to 22 year olds. And Bishop’s dialed-in, always-focused mindset on race day was the right formula.

“For [Bishop] to come in and have those efforts of trying to diversify both the sport and then bring in an outlet for leadership,” Bailey said. “I think it was pretty tremendous.”

* * *

For Bishop, coaching in the Little 500 has been about more than just the championships he’s won. He reinvented race-day strategy, created a successful all-minority team, diversified the Little 500 fan base and saved lives.

Moving forward, the Little 500 will be without one of its most impactful leaders.

Bishop accepted a role as an assistant coach for distance runners on the University of Nebraska track and field teams. Bishop and Jet Blach wore Michael Jordan-inspired Last Dance t-shirts to their 2021 Little 500 championship race, but when asked if his Little 500 coaching career was officially over, Bishop didn’t close the door completely.

“Someone once said, ‘Never say never,’” Bishop said.

And although Bishop has moved on to coaching a different sport in a different state, he still holds onto lasting memories of the relationships built through coaching Team Major Taylor, Jet Blach and Delta Tau Delta.

Just over two years ago, Bishop was at an event when his phone rang. It was Kenny Burgess, who Bishop hadn’t talked to in a number of years. Burgess invited Bishop to Nick’s English Hut to have a beer with him and his former Team Major Taylor teammates.

It started as a long night of sharing old stories with pictures of past Little 500 races decorating the walls surrounding them. But when a couple guys got up to get another drink or go to the bathroom, Burgess pulled Bishop aside.

“Hey, we’ve kind of butted heads over the years in the past,” Burgess said. “But you saved my life. I have no idea where I would have been if not for what you did.”

In Bishop’s mind, he thought about what would have happened if he let Team Major Taylor die after its first race in 1992 when it was lapped 30 times. He couldn’t just send Kenny Burgess on a bus back to South Central Los Angeles. He couldn’t break the promises of building a successful team, expanding diversity, graduating riders and being a lifelong resource of support. He didn’t have a choice.

So when Courtney Bishop reflects on his 30-year Little 500 coaching career, it’s about more than success on the cinders of Bill Armstrong Stadium. He’s fulfilled by watching once-unconfident kids turn into champions, especially in a sport as demanding as cycling.

“All of a sudden they start getting success … and it’s like they’re completely different people,” Bishop said. “Now here comes that confidence, that belief that they can do things that they never in a million years thought they could do. It changes their lives.”

Editor's note: This article was originally published on April 21, 2022 and edited on May 2, 2022.