Indiana forward Kiandra Browne eyed the white netting on Nov. 14 in the midst of an offensive dribble drive play against No. 13 Kentucky. But as she sliced through the paint, part of her identity was left behind. Browne abandoned the play, collapsed to the floor and reached for her hijab.

The four other Hoosiers on the court weren’t concerned about the ball, though. They rushed to Browne’s side and surrounded her, making sure she was hidden from the flock of jubilant fans in Simon Skjodt Assembly Hall. Although there was still a game to be won, Browne was the priority at that moment.

During the offseason, Browne told her teammates she was nervous about beginning this season with an added wrinkle: her hijab — a head covering allowing Islamic women to retain their modesty, morals and freedom of choice.

“I’m scared,” Browne said. “I don’t know what’s going to happen if my scarf comes off. Like am I going to go for the ball...am I going to go for my scarf?”

Indiana junior forward Mackenzie Holmes never gave it a second thought. She gathered the team in the locker room: “Everyone, if KB’s scarf comes off we’re all getting around her.”

The team agreed, “Yeah, of course, we got you.”

Relief brought a smile to Browne’s lips.

“Hearing that made me tear up because I was like, ‘Wow.’ I was so scared,” Browne said.

Browne converted from Christianity to Islam before she began her sophomore year, and was nervous about the reaction she’d get from all the eyes that are constantly on her. At the same time, she was dealing with the demanding process of rehab due to offseason hip surgery.

Whether she’s switching sports, moving between countries, or changing the way she pursues her faith, Browne has never felt more welcomed by a school and by a team. She’s embracing her role as the sixth man for one of the top teams in women’s college basketball, and all of life’s realizations that come her way.

Sheryl White’s gaze swiveled between the numerous doctors, visitors, patients and IV bags seen during a 12-hour-shift at the hospital. The buzzing fluorescent lights in the ceiling had become a never-ending vibration in her eardrums, and the faint dripping sound from the transfusion bag began to hush. The shift ended, and it was time to go home.

But White’s day had only just begun. Being the mother of two, the priority on her mind now was on her daughters Kiandra and Serena Browne.

As a nurse, White’s days were nonstop, even after clocking out. White dedicated all her free time outside of work to making dinner for Kiandra and Serena and rushing them to sports practice day after day. But she never complained.

When Kiandra and Serena had a game the same day, White would be there for both. If they both had Tuesday practice hours away from each other, White would pick them up on time for both.

“She’s a trooper,” Kiandra said. “My mom’s the best, she sacrificed so much.”

No matter what sport Kiandra and Serena were pursuing at the time, White was all in. And her mentality echoed through Kiandra as the athlete inside of her was emerging.

“She says, ‘Don’t do anything half ass,’” Kiandra said. “That was always her little saying for me.”

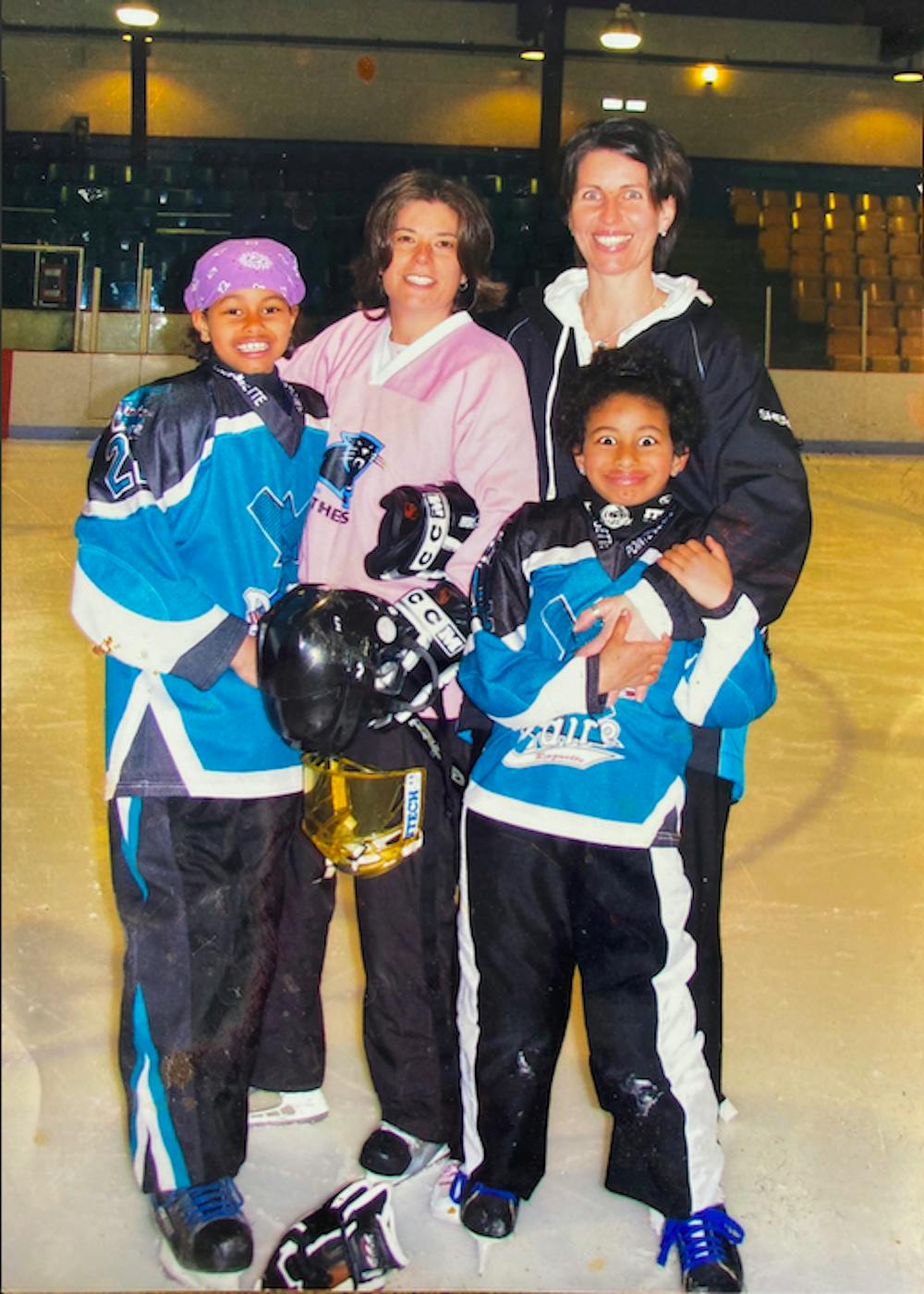

Ringette, a non-Olympic, female ice sport similar to hockey, was Kiandra’s athletic focus for the majority of her childhood growing up in Montreal. Kiandra put on her first pair of skates before Kindergarten, and the rink was the first place she began to learn more about herself as an athlete.

Kiandra learned that she is aggressive and in-your-face and spent a lot of time thinking about these things in the penalty box.

“Ringette is a non-contact sport...but I made it a contact sport,” Kiandra said. “So I was like, ‘OK, maybe this isn’t for me.’”

Kiandra dreamt of representing her country on the highest stage in the world at the Olympics one day, so she scratched ringette and began playing soccer at 14. Her physical play — and 6-foot-3 frame, with skates on, as a 10-year-old — might have contributed to the switch, too.

Through soccer, Kiandra learned that she’s uncoordinated — very uncoordinated. She struggled running and kicking the ball simultaneously, and instead, realized she was better at jumping in front of shots. Kiandra became the team’s goalie — on a travel team full of college girls — provoking her innate competitiveness.

“It was an awesome experience because I was getting my butt kicked all the time and I didn’t want to lose,” Kiandra said. “My mom would always tell me, ‘Kiandra don’t worry, they’re like six years older than you.’ I’m like, ‘I don’t care.’”

But soccer wasn’t working out, and still in pursuit of the sport for her, Kiandra picked up a basketball after practice one day. Soon enough, she’d leave the grassy fields for the hardwood, trekking the same path as her mother and grandmother who also played basketball.

When entering the ninth grade, Kiandra was recruited to the basketball team by head coach Dan Lacasse at École Secondaire St-Laurent, a powerhouse high school that traveled to the United States nearly every weekend for premier basketball competition.

Choosing a sport to concentrate on was a requirement for students, and practice before and after class was the only option. The entire backbone of St-Laurent was sports.

“Practice was literally one of my four period classes,” Kiandra said. “We put all our eggs in one basket, we went all in with basketball.”

The proletarian way of work and an all-or-nothing culture at the school — similar to basketball in Indiana — are the roots of Kiandra’s unconditional love for the sport. The environment of St-Laurent allowed Kiandra to reap the rewards of basketball with quick improvement, and she envisioned herself shooting 3-pointers in front of crowds of thousands. And four years later, she’s doing just that.

Maybe all that time spent in the penalty box built something. Maybe all the tedious drives to and from Quebec for soccer practice were worth it. And maybe the buzzing from the hospital lights weren’t so bad after all.

The fate of the uncoordinated, ambitious young athlete was inescapable. Kiandra was meant to be a basketball player.

A one-way plane ticket from North Carolina to Quebec is all Kiandra wanted in March 2020. Because international borders were shutting down, she made an abrupt escape back to Montreal.

Not long after her flight landed, Kiandra and White took off for a nighttime drive through the quiet borough of Saint-Laurent. Kiandra had spent the last year away from home, playing basketball and being the team’s leading scorer at Winston-Salem Christian, a prep school in North Carolina. There’s much the two needed to catch up on — COVID-19, basketball and her college recruitment.

Kiandra’s mind was previously fixated on returning home because of the pandemic, but now the only thing on her mind was a phone call — one which could change her life.

Around 9 p.m., a blanket of stars settled over the West Island of Montreal. Gleaming orbs of light flashed past Kiandra’s eyes in a blur through the windshield.

White parked the car and the two sat and talked for hours until their conversation was interrupted by a phone ring. Little did they know, it was the ring.

“I’m like, ‘OK mom, hold up, someone’s calling me,’” Kiandra said. “I look at my phone and it’s an unknown number, and I’m like, OK, whatever,’ so I answer the phone.”

On the other end of the line, Kiandra heard the voice of Indiana assistant coach Glenn Box.

The phone call determining Kiandra’s future had finally arrived and her restlessness slowly began to dissipate. She and White sank into the nylon seats of the car, intently listening to Box’s words.

“We need to talk,” Box said. “I need to get you on a Zoom call with coach [Teri] Moren. We all want to meet you.”

At a time where all hope seemed to be lost in the world, the stars in the West Island may have aligned for Kiandra that spring night.

White drove Kiandra through this borough en route to countless basketball games as a kid, and it’s the same one where she realized her Division I basketball dreams were about to come true. And a few weeks later, she found herself in Bloomington — awaiting the basketball journey she’d always hoped for.

About a week after Indiana’s heartbreaking loss to Arizona in the NCAA Tournament, Kiandra found herself lying on an operation table gearing up for hip surgery. Two months later in May of 2021, she’d leisurely make her way into Assembly Hall. She saw Aleksa Gulbe, Ali Patberg, Mackenzie Holmes, and others running ladder drills from one end of the court to the other.

While her teammates were preparing to avenge an Elite Eight loss, all Kiandra could do was tread down the long road to recovery. She couldn’t run agilities and she didn’t hear the voices of Box and Moren telling her to get her head in the game during practice. Rather, she was stuck in the weight room lifting dumbbells four days a week, while director of athletic performance Kevin Konopasek yelled, “Push-pull! Push-pull!”

Furrowed brows and deep sighs would become the norm for Kiandra as she was restricted from her biggest love: basketball. Kiandra said she isn’t used to being limited, but the surgery may have been a blessing in disguise because her upper body had always been a bit weaker.

“I feel like I’m the strongest I’ve ever been, really,” Kiandra said. “Being able to focus on my upper body for so long helped a lot.”

After averaging 2.1 points and 8.3 minutes per game during her freshman season, Kiandra has taken on a bigger role this year after a rehab process that put her in the best shape of her career.

She’s now playing 13.8 minutes a game on what could be the best Indiana women’s team of all time. Typically first off the bench, Kiandra has learned she needs to be ready for Moren to call her number at any moment.

“KB always just plays inside of herself,” Moren said. “She’s a very emotional kid, so she’s always hunting out opportunities to position herself to take charge. She knows her role and she does her job.”

Every time she throws her hands in the air — jumping off the bench, hyping up her teammates, or even yelling gibberish at times — the emotion behind it means something. On and off the court, basketball is Kiandra’s life.

“If I’m going out there and sacrificing my body, I just want to give everything,” Kiandra said. “I don’t know the right words to exactly put it, but I want to give everything to basketball.”

The desire to intensify her game has only increased since being in Bloomington. Playing with Berger, Holmes and Patberg — three veteran, All-Big Ten players — has brought the bulk of Kiandra’s inherent competitive nature to the forefront. Moren even called her Indiana’s “best screener by far.”

“Just being around that kind of energy is contagious,” Kiandra said. “I feel like that just shows me how much you have to gain being in a place like this.”

While the talent of the Patbergs, the Holmes and the Bergers of the world might speak for themselves, the small moments shared between teammates have spoken louder to Kiandra than any buzzer beater ever could.

When Kiandra was lying on the court, hijab-less, against Kentucky, she realized that it didn’t matter how others viewed her because she was surrounded by the girls who understood her the most.

“This is definitely the first team that I’ve been on that’s been good in the locker room,” Kiandra said. “There’s no fighting, no bickering, none of that stuff. Everyone genuinely cares about each other.”

No matter what religion she’s practicing or what she’s wearing on her head, her teammates still love and accept her unconditionally. And she’s found support inside and outside Indiana’s basketball program.

Over a year ago, after her Hoosier debut, Kiandra found herself pondering the meanings of life and why certain things happen. Seeking out her most authentic self, she converted from Christianity to Islam, realizing that she better identifies with that faith.

“One thing about KB, she really tries to stay who she is,” Moren said. “She doesn’t try to be anybody she’s not.”

Kiandra said she still believes in the same God after her conversion, but the only difference now is that she worships in a different way. Islam has allowed her to become much stronger in her faith and connect with God on a deeper level, attributing a big part of her basketball success to her relationship with him.

“The abilities that he’s given me allows me to succeed every day,” Kiandra said. “I’m grateful for that, I really am.”

While Kiandra played last season with her hair down, she walked into Assembly Hall this year wearing a hijab. Nothing negative about her conversion has ever come about at Indiana, but Kiandra’s basketball family hasn’t been her only support system.

The Islamic Center of Bloomington has given Kiandra a platform to pour the rest of her emotions out into her passions outside of basketball. Often, she'll give talks at the mosque about empowering women and serves as a role model for many, especially young female minorities in the community.

Kiandra’s passion prompted her to create an organization of her own last year with women she’s befriended at the mosque: Muslim Women at IU, a club for everybody — Muslim or non-Muslim — to support and empower women in their communities. Since forming this organization, Kiandra has been speaking about her experience being a collegiate, minority female athlete.

Mothers have even asked Kiandra for advice about the importance of sports in their children’s lives. Kiandra has spoken on this topic a lot, and feels basketball is a big reason why she has excelled in school, and she strives to support the next generation of student athletes.

“I’m very passionate about being an advocate for anyone who might not want to speak for themselves or who are scared to,” Kiandra said. “I’ll put myself out there in order to empower other people.”

Kiandra is fulfilling her dream in a new country now, but when she wants a taste of home, she pulls up videos of her and her mother practicing layups back in Montreal. Kiandra’s game has grown since her youthful years, but these videos give her perspective on how far she’s come since then.

“I’m like, ‘Oh my gosh, Kiandra, what were you doing?’” Kiandra said.

Nevertheless, she enjoys the nostalgia brought on by watching her 14-year-old self in these videos. They show her practicing on an outdoor court with her mother, just after she’d decided to quit soccer.

The fine-grain, orange leather coating of the basketball spun through Kiandra’s palms, bouncing from one hand to the other. She ran to the paint, leapt and scored a layup.

It was a proud moment for White, as she saw her little girl experience the butterflies and childlike excitement about basketball that she once had. From then on, Kiandra didn’t have to search anymore -- she had found her sport.

Standing together on the outdoor court, Kiandra turned to White after making the layup, saying, “OK mom, let’s play basketball.”