Ryder Anderson had just finished a conditioning session when he heard an unusual noise coming from the side of the field.

It was during Indiana’s fall training camp, still the “dog days” of the Midwest summer, as Anderson describes it. It’s no surprise then that Anderson and his defensive line teammates, who had finished up some daily conditioning, were a little bit tired.

That’s when Anderson heard the sound, a deep heaving noise. He whipped his head around to see what it was.

There was Weston Kramer, head down, throwing up into a trash can.

“Wes, you good?” Anderson asked.

“Yeah, I’m good,” Kramer responded. “Let’s go.”

Kramer quickly returned to the field. He didn’t miss a play. In the next drill, he made a tackle for loss.

“Weston,” Anderson said, “is not going to miss a play.”

This was just one of the many moments that have made Kramer’s intensity somewhat legendary around the Indiana locker room in just his first season with the Hoosiers. There’s also the fact that Kramer slaps himself in the face before lifting weights to get himself motivated. Or that his cleats sometimes squish when he walks because he’s so drenched in sweat.

Kramer’s coach at Marmion Academy in Aurora, Illinois, Dan Thorpe, says “he’s a different breed.” Anderson says “he’s always got this look in his eye.” Indiana defensive line coach Kevin Peoples puts it like this: “He really has just one speed.”

Kramer’s tangible and intangible traits have made him an indispensable part of Indiana’s defense, a unit that has been a bright spot amid the team’s mediocre start to the season. Kramer, who only had two offers out of high school and who became a graduate transfer this offseason before committing to Indiana, is thriving because of his relentless nature. At Indiana, he currently ranks seventh on the team in tackles with 16, while adding a tackle for loss and fumble recovery. His overall impact, however, can’t be quantified.

“Just his effort, it’s that way every single day,” Indiana head coach Tom Allen said. “I don’t think that I’ve ever seen a kid at this level practice as hard as he does. Every single day. It does not matter. To me, that’s infectious, it’s contagious. I love it.”

When trying to understand Kramer, perhaps it’s best to start with two of the tattoos on his left arm, and the way he describes them. Inked on the outside of his bicep is a “fierce bear,” its jaw wide. On the inside, there’s a “wise owl,” its gaze focused.

***

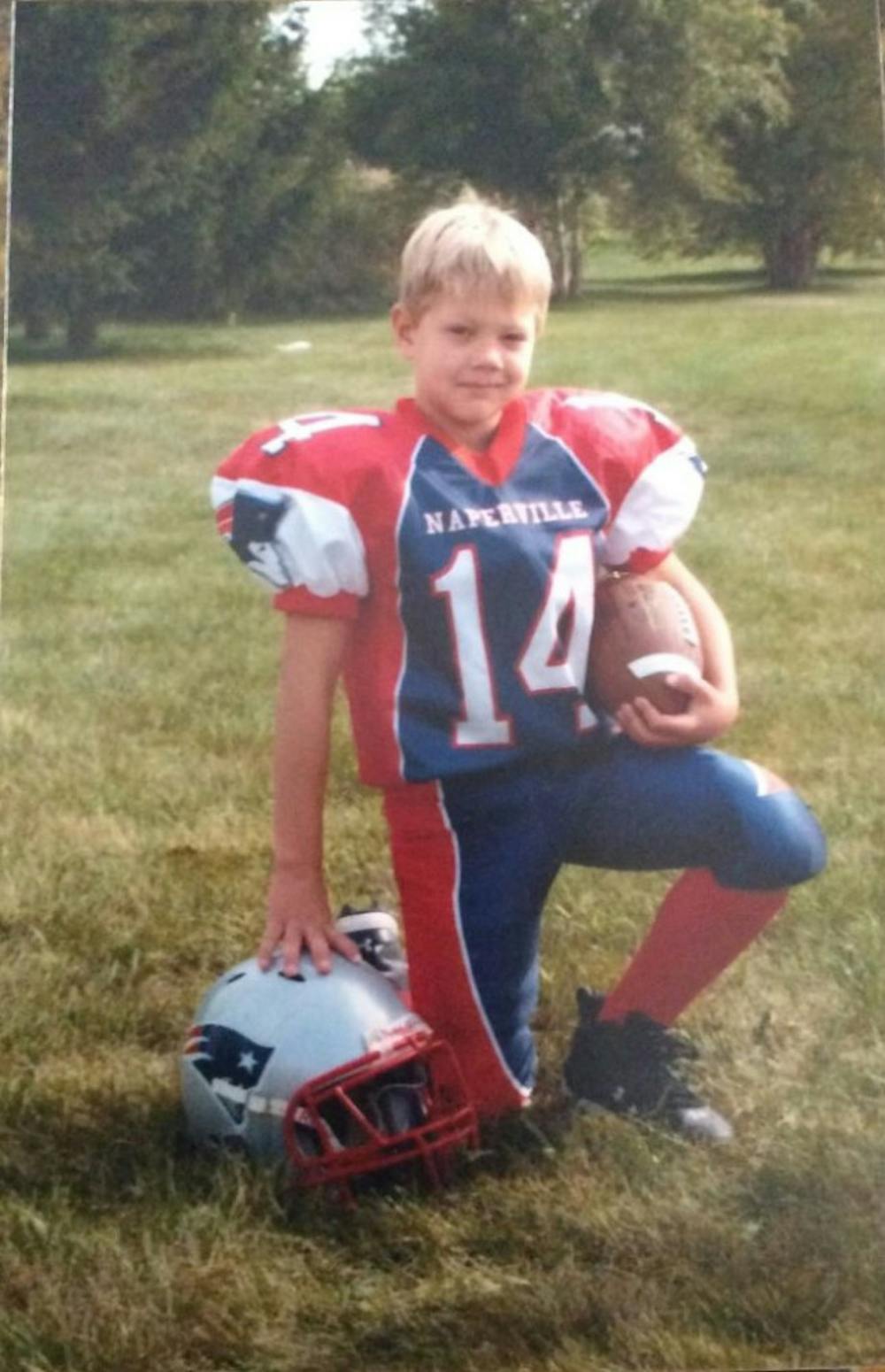

As a kid, Kramer’s parents signed him up for all types of sports so he’d use his energy in a constructive way. He joined the swim team when he was four. Later, he started playing hockey, football and baseball. Back then, though, he wasn’t close to the 6-foot-2, 290-pound wrecking ball he is now. As a freshman in high school, he weighed just 170 pounds. Before that, when Kramer was younger, his mother Kristine had to sew up his bathing suit just so it wouldn’t fall down.

Regardless, it quickly became evident that Kramer liked contact. In pee wee football, his coaches used to get mad at him because he hit too hard. When he played running back, he’d often drag tacklers on his back across the field. In baseball, he’d sometimes truck the first baseman or catcher when speeding down the basepaths.

“He was just so excited to get to the base,” his father Richard said.

Kramer also displayed a certain level of determination. In eighth grade, Kramer was playing running back when the other team intercepted a pass. Kramer raced 70 yards down the field, caught his opponent from behind and forced a fumble, which his team recovered.

This trait was apparent off the field too. When Kramer was trying to learn how to ride a bike, he told his mom that he didn’t want any help and that she couldn’t run beside him for stability. At first, he’d teeter over and go crashing down. But then he’d get right back up and try again. Soon, he mastered it.

“It took him probably 20 minutes,” Kristine said.

It was around when Kramer started playing varsity football as a sophomore in high school that he started to bulk up. He guzzled down 2,000-calorie protein shakes every night before bed. He ate hamburgers, chicken and Mexican skirt steak.

“The butcher always knows when my boys are coming home,” Kristine said.

Kramer joined the weightlifting club, where he’d deadlift 500 to 600 pounds, dripping in sweat, but a smile on his face nonetheless.

“He doesn’t need flashy uniforms or flashy weight lifting equipment,” Thorpe, his high school coach, said. “Open the door and get out of his way.”

During games, he’d play offensive and defensive line and nearly always decline a break when the coaches offered it to him. He was so exhausted after games that he’d come home and soak in an ice bath.

There were times, though, when Thorpe had to pull back Kramer’s ferocity. It’s a known rule among football programs that you don’t hit the quarterback during practice. But Kramer wasn’t able to control himself, sometimes tackling the quarterback, who even wore a different color jersey to signify he should go untouched.

There’s a juxtaposition, though, to Kramer’s personality off the field. He’s described as “fun-loving” and “extremely personable.” He once dressed up in clown costume for Halloween. He helped organize school spirit events, where, one time, he put together a mock WWE wrestling event in the cafeteria and walked around with signs as if it was being televised.

It all relates to how Kramer treats others. If the athletic department needed help, he’d almost always volunteer. One time, he led a group of classmates in putting up Christmas tree lights around the city. In middle school, a girl on his football team was facing a barrage of trash talk from their opponents. Kramer stepped in front of eight or so opposing players and told them to leave her alone. They did.

“He was always the first one to help someone out,” Kristine said.

***

The first call sounded something like this: “Oh my god, this kid’s a beast.”

It was a coach from Northern Illinois, live from a summer recruiting camp, dialing Thorpe about Kramer.

“I told you so,” Thorpe responded.

A few minutes later, the phone rang again.

“We just made him get 12 reps in a row and he met every kid and he’s ready for the next rep,” Thorpe recalls an NIU coach saying.

“I told you so,” he responded.

A few minutes later, it rang again.

“We can’t believe no one’s recruiting him,” an NIU coach said. “We’re going to offer him right now.”

“I told you so,” Thorpe responded.

It was the summer heading into Kramer’s senior season. He went to his first big camp at NIU, where around 25 to 30 schools and 300 to 400 players were in attendance. Kramer did what he’s always done. He blew up plays and threw opponents to the ground. The college coaches were giddy, to the point where they shouted his name across the field.

Despite tallying a dominant 134 tackles, 40 for loss and six forced fumbles throughout his junior and senior high school seasons, Kramer was only regarded as a 2-star recruit and ranked as the 3,857th player in the 2017 class. It could be explained by the fact that he was somewhat undersized. Kramer was listed at 6-foot-2, but Thorpe estimated he was closer to 6-foot and didn't possess the long, athletic frame that some coaches gush over.

But then Thorpe’s phone started receiving call after call from an NIU coach.

NIU did offer him. And Kramer, who grew up attending NIU games with his parents, committed to the Huskies.

In four seasons at NIU, Kramer appeared in 45 games, including 30 starts, where made 97 tackles and tallied 3.5 sacks. In his senior season, he was named second-team All-MAC. It didn’t, however, all go smoothly. In four seasons, he played for two different head coaches and three different defensive line coaches and three different defensive coordinators. Amid those changes, Richard said, Kramer tried to keep his teammates together and be the example.

“When I was at Northern Illinois, I just trained very hard every single day,” Kramer said. “I always just tried to make myself better at everything that I did.”

In the offseason, he entered the transfer portal to play at a high-profile league like the Big Ten. This time around, programs like Iowa, Texas and Michigan State all showed interest. But he ultimately chose Indiana, his father saying that he loved Peoples’ demeanor. Plus, Kramer’s personality fit right in with the L.E.O. culture.

“The first time I talked to coach Allen, I committed right after that just because I just really bought into what he was saying, the energy he brought to that conversation,” Kramer said.

Kramer quickly moved up the depth chart into the starting role and became a key force on the interior. He had seven tackles against Iowa. Then a fumble recovery against Idaho. He recorded five more tackles against Penn State.

As Indiana tries to get its season back on track, Kramer’s drive hasn’t wavered. Undersized or not, underrecruited or not, his effort has finally made a resounding statement, one that’s starting to get the attention that he deserves. On Saturday, Kramer will be tasked with trying to stop Michigan State’s Heisman candidate running back Kenneth Walker III.

Kramer will do it with the tattoos wrapped around his left arm, an accurate representation of who he has become. The “fierce bear,” its jaw wide. The “wise owl,” its gaze focused.

“I just got them,” Kramer says, “Because I see it as myself a little bit.”