Marty Freeman waited and waited, but nobody came, so he waited some more.

It was March of 1985 and Freeman had just wrapped up a workout at New Castle High School, but nobody came to pick him up. When he had no way to get home, New Castle football coach Tom Allen Sr. provided a ride, bringing Freeman back to the Allen household, where they served him dinner.

Later that night, Freeman learned that his grandfather, the most important figure in his life, was in the hospital. The next day, he passed away.

From then on, the Allen family took Freeman in as one of their own, providing him with the family structure that he needed coming from a single-parent household and after losing his grandfather.

Freeman also became best friends with the family’s third child out of four, Tom Allen, also known as Tommy. Tom and Freeman went bowling and golfing. They attended Bible club. They reviewed film from football. The Allen family introduced him to putting peanut butter on pancakes, which he still does to this day.

“It’s sort of ironic that we’re such close friends because growing up I was from a single-parent household and if you looked at the two of us I don’t think people would’ve put us together,” Freeman said. “Much less a friendship that has lasted decades.”

Tom was raised on foundational values passed down from his parents: treating people with respect, honesty and integrity. It was during Tom’s childhood in Lafayette and New Castle that guiding elements of his life — family, faith and football — were instilled.

“That’s how the lord made us,” Tom Sr. says.

The Allen family was open to helping everyone, and that’s what Tom saw growing up. One time, the well at the church broke, so the Allens went to fix it. They hosted big meals for the teams that Tom Sr. coached, where they cooked chicken, slaw and corn on the cob. They became a second family to others in the New Castle area, including Jeff Estes, who accompanied them to church every week. Years later, Estes became a pastor, a path he wouldn’t have taken had it not been for the Allens.

“Love each other, but we didn’t call it L.E.O. (yet),” Tom’s mother Janet said. “He grew up doing that.”

Three decades later, it’s what has allowed him to build unprecedented success as the head football coach at Indiana, where the Hoosiers will kick off this season on Sept. 4 against Iowa. In a world sometimes filled with hate, the driving force of the program is a simple acronym: L.E.O. — Love Each Other.

Tom has become somewhat of a transcendent figure because of his undeniable charisma. He frequently acts with a child-like jubilation, even crowd surfing on his players after last season’s historic win against Penn State. His philosophies are being taught in some Indiana elementary school classrooms.

“It’s bigger than football to me,” Tom said. “...I don’t want to be known as a guy that coaches the ball. I want to be known as a guy that impacts lives and makes a difference.”

All of who Tom is, started a half century ago.

“He hasn’t changed a bit,” Freeman said.

***

Tom Allen was sprinting down the sideline at Memorial Stadium.

Last November, with just under six minutes remaining in the game, safety Devon Matthews picked off a Michigan pass. The Hoosiers were up by 17 with the ball. They were about to beat Michigan for the first time since 1987. And Tom could feel it.

So here came the 51-year-old galloping down the sideline. Tom leapt up into Matthews, his bare cheekbone crashing with helmet. Matthews was knocked on his back. Tom fell on top. After the win, there was a bloody gash on Tom’s cheek.

“I don’t think he broke it, but it doesn’t feel very good right now,” Tom said after the game. “ But bottom line is I don’t really care. I just love this team.”

Even as an infant, Tom had boundless energy. A few days after he was born outside of Lafayette, Tom’s blood wasn’t clotting properly, so the doctors gave him medication and tied down his feet to ensure he was stable. But Tom didn’t like it. He kicked and kicked until his heels rubbed raw. By the time he came home, there were red spots the size of a coin on his heels.

As a youngster, Tom’s parents described him as a “busy little boy.” Once, before Tom was even in grade school, Tom Sr. peered out the back window of the house and saw a neighbor looking toward the Allen house, chuckling to himself. When Tom Sr. went outside to see what the commotion was, there was Tom and his older brother Nathan climbing up and down a ladder to the roof and tossing a garden tool onto the yard.

Sometimes Tom’s energy worried his parents. He often played hide and seek, where he’d disappear around the house, hoping others would come look for him. One time, Tom was gone for so long that Janet was ready to send a search party out to the cornfields, thinking that he’d gotten lost in a nearby farm. But before she went out, Janet checked the closet, Tom’s favorite hiding spot, one last time. Sure enough, there he was, smiling from ear to ear.

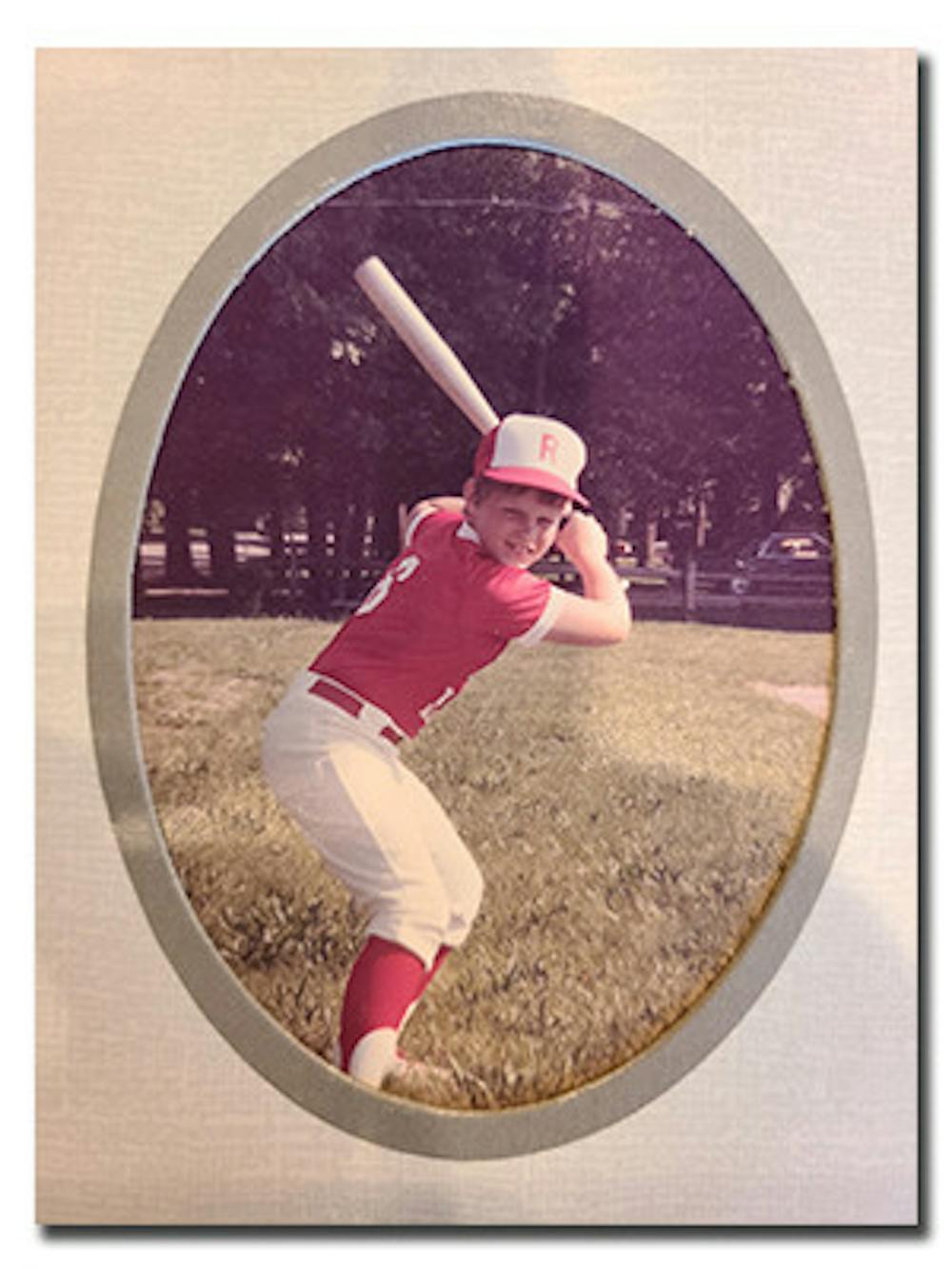

Much of this exuberance was also invested in sports. Kids around the neighborhood met in the Allens’ backyard to play football. They played everything — tag, basketball, baseball — and it gave Tom the social interaction he craved. Everyone wanted to be on his team. Everyone wanted to be his friend. Tom Sr. gave his son the nickname “Pied Piper” because of how others followed his lead.

Inside the house, Tom Sr. put down tape in the shape of a box on the living room floor. Tom and Nathan suited up in pads and helmets and tried to knock each other out of the square. They also did a drill where they started on opposite sides of the doorframe and tried to push each other through the opening.

“They were always playing something,” Janet said.

***

Tom Sr. wanted to make sure his kids knew about hard work. And not just being told about it, but living it.

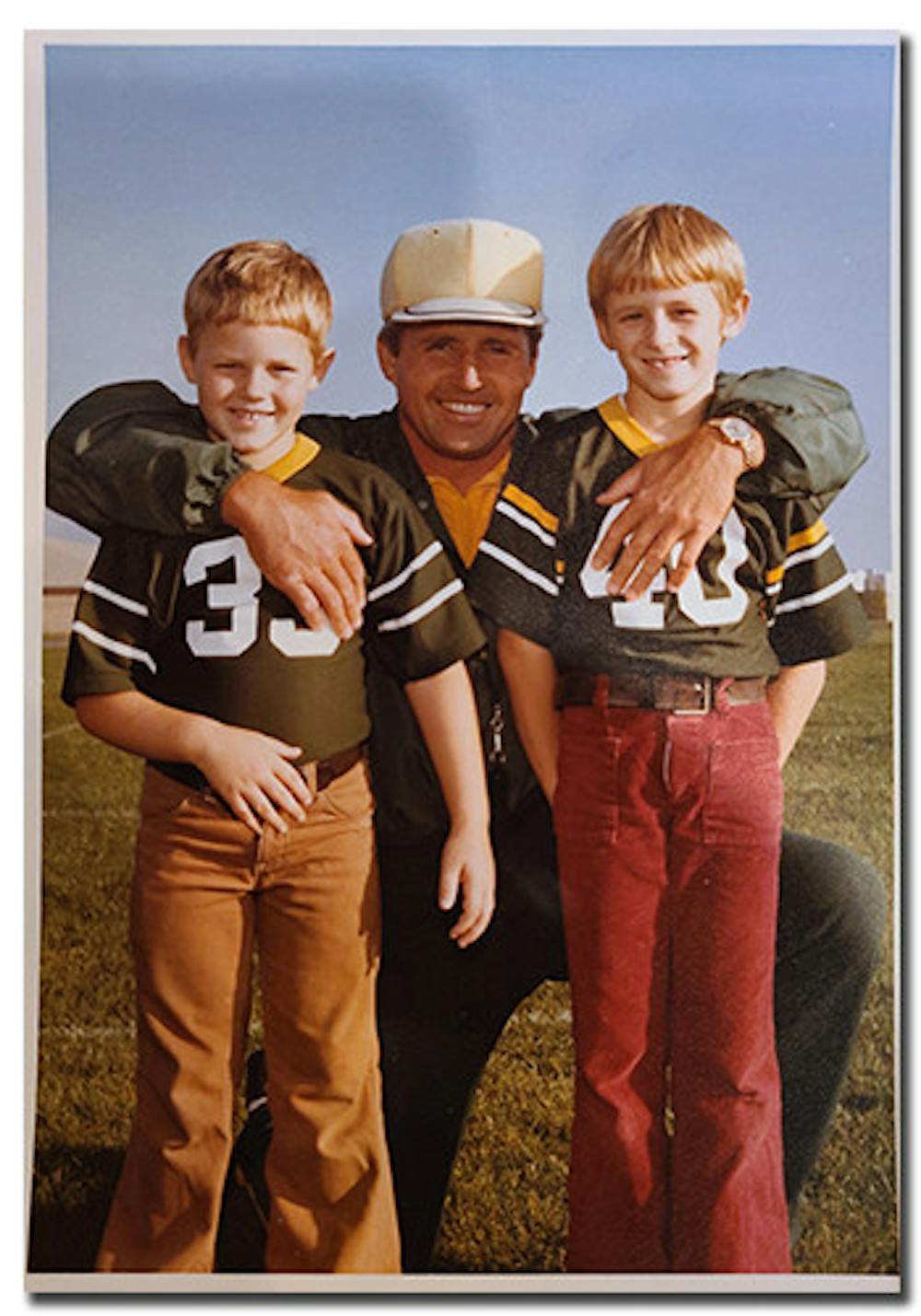

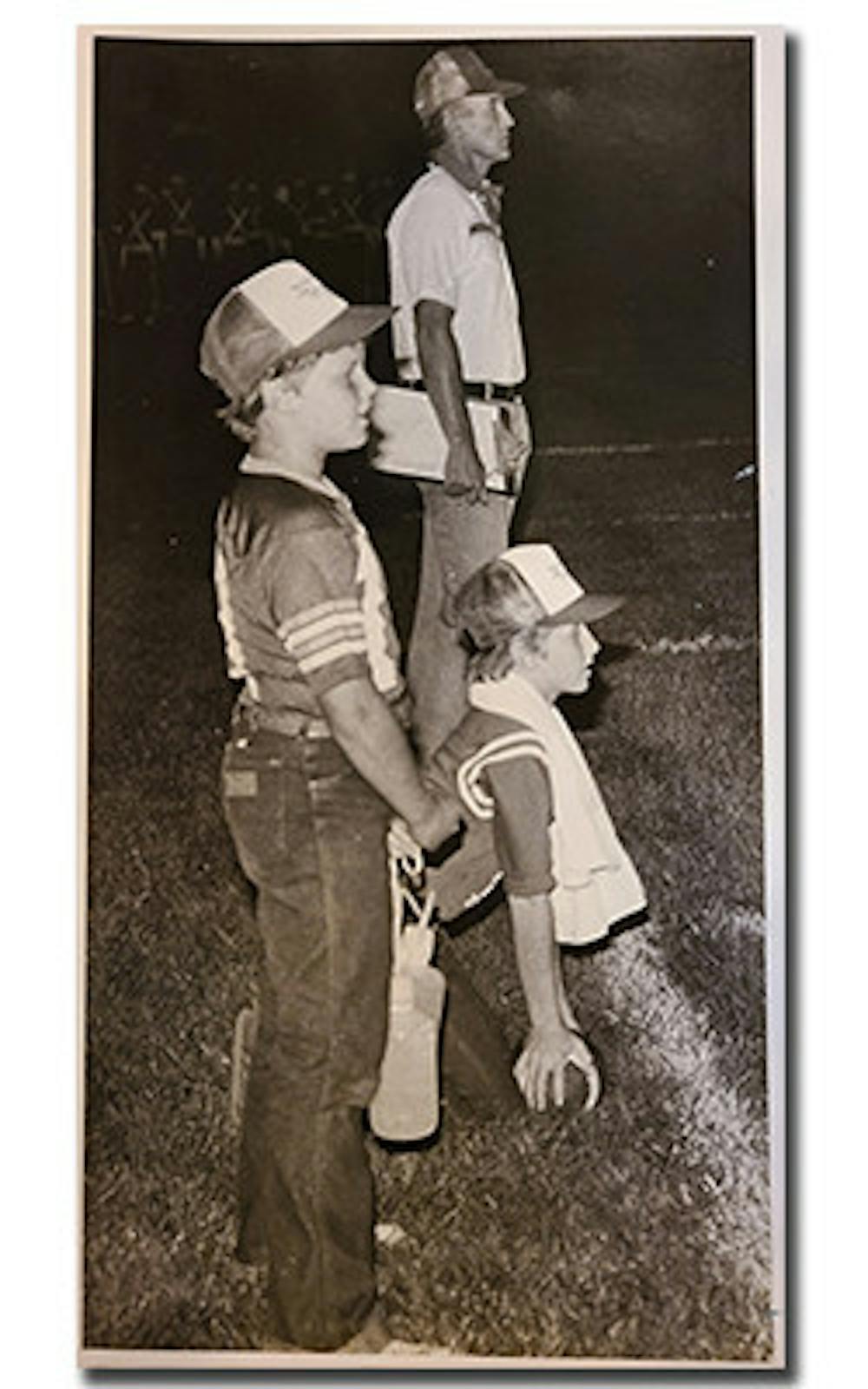

When they were old enough, Tom Sr. took Tom and Nathan to football practices. They did all the work of a team manager: dragging out tackling dummies, riding on the bus to games, helping players with anything they needed. What people noticed most about Tom was his demeanor. He’d look you in the eyes when talking. He always had a smile on his face.

“It’s still that way today,” Tom’s high school wrestling coach Rex Peckinpaugh said. “You hardly ever saw him frown.”

Tom Sr. also worked as a carpenter and, when Tom and Nathan were in high school, he brought them to work over the summer, so they could save up money for college. They built garages and painted houses. They fixed roofs. They laid bricks and poured cement. After working in the scorching hot Indiana summer, they put their feet in cold water to alleviate the pain of their blisters.

This work ethic carried over to Tom’s athletic career. He played football and wrestled at New Castle. Regardless of his busy practice and game schedule, he was at the top of his class academically. Tom would study until 12:30 a.m. and then be at the school by 6 a.m. to run two or three miles.

At wrestling workouts, Peckinpaugh’s goal was to leave his wrestlers “in a state where they had a hard time walking.” But after practice, Tom and Nathan would go to get another lifting session in. It was the same over the summer, where, after fixing roofs and pouring concrete all day, Tom would make it to almost every wrestling and football workout at night.

During his senior wrestling season, Tom was beaten decisively by a rival. The headline in the paper the next day implied it was almost solely Tom's fault the team lost. In the following weeks, Tom studied more film. He was more focused during practice. Later in the season, Tom faced the same rival and pinned him. He went on to place third in the state meet.

“I’d hate to be the person that beats Tom Allen,” Peckinpaugh said.

Tom led the team by example. During sprints at wrestling practice, despite weighing more than 50 pounds more than some of his teammates, Tom was always one of the first to finish. He was also vocal, frequently yelling encouragement. If someone needed help after practice, he was willing to stay. He learned those guiding principles from from his parents and his faith.

“Even back then, he practiced that idea of L.E.O.,” Peckinpaugh said. “He was loved by everybody and he loved the people on his team.”

“Tommy just makes you feel loved.”

***

With the same conviction that he used to fix roofs and pour cement, Tom ascended up the coaching ranks. First, it was high schools: Temple Heights and Armood in Florida, then Ben Davis in Indiana. He eventually earned a job at Wabash College, then made stops at a handful of other schools, including Ole Miss and South Florida. He was brought on staff at Indiana in 2016 and, later that year, was named the head coach.

Ever since, Tom has taken a historically underwhelming program to unparalleled heights, despite being frequently doubted. It started off with consecutive 5-7 seasons but quickly grew into historic success last season, rising up the rankings and creating a certain bravado for the program.

Regardless of his success and clout, Tom is still connected to those from his childhood, even if it’s no longer through sports. In Tom’s early coaching years, Estes, the childhood friend turned pastor, needed financial support to start a church. Despite how little they had, Tom and his wife Tracy made a “significant” donation, an exact amount Estes wasn’t willing to reveal. The church has now been around for 19 years and has a community of more than 250 people.

“Nobody else knows that,” Estes said about the donation. “Nobody else would know what they do and that type of sacrifice. They don’t tell anybody that stuff. I’m the only one that knows what they did for us.”

Last winter, Estes was in a life-threatening car accident. He fractured his pelvis, broke his ribs, had serious internal bleeding and his spleen removed. He couldn’t walk. But through it, Tom was there. They talked on the phone, and Tom wrote notes. They laughed together, cried together.

“You’ve got to have the lord and you’ve got to have grit,” Estes recalls Tom’s message.

Estes has recently started walking again and made significant strides in his recovery.

“I know that when you go through really hard times, God uses people,” Estes said. “Tommy and Tracy have been some of those significant people to help us.”

With magnified expectations entering his fifth season at Indiana, who Tom is, and what he believes in, hasn’t wavered. He recruits and coaches with the same determination as his high school self, the one who had blisters on his feet from fixing roofs and the one who woke up at 6 a.m. to run after studying until midnight. He treats his players as family, just as he did with Estes and Freeman years before. He chest bumps his players after big plays and crowd surfs after wins with an unquestionable joy, almost as if he’s still a kid, tossing garden tools off the roof and playing football with full pads inside of the living room.

“If he’s any different than he was back years ago, I’m not seeing it,” Peckinpaugh said. “He’s just Tom Allen.”

“He’s just Tommy Allen.”