Al Stewart’s “Time Passages” played in the background as black and white images appeared on the screen in front of a group of over 70 seated at circular tables. It was quite fitting.

Years go falling in the fading light. Time passages.

They wore the same ring. A gold band around a wrinkling finger, the words “Indiana University” curved around the center hugging the red face of the ring, a gold IU trident in the middle.

They wore white hats with a red “Holiday Bowl Champions” logo on the front covering heads of graying or balding hair, and red polos with the same logo on the left, over their heart.

The youngest players were in their 60s. The oldest coaches in their 90s. They laughed and reminisced, telling the stories from years ago. Stories about football and kids and the years gone by. Stories that have gotten better with age. Stories from a glory left behind in decades past.

The 1979 IU football team, a “brotherhood of warriors” as team captain Terry Tallen put it, gathered in the Henke Hall of Champions 40 years after Tim Wilbur’s punt return touchdown in San Diego.

Wide receiver Steve Corso had the same energy as his dad and IU head coach Lee. Running back Mark Harkrader’s 5-foot-7-inch frame hidden between his taller teammates, just like back in his day behind his offensive line. The time since their college days was evident on the faces of the players. But some, like Tallen, didn’t look like they missed a day in the weight room.

Quarterback Tim Clifford led the 1979 team as it walked behind the 2019 group, entering the stadium before facing Eastern Illinois. He carried the Holiday Bowl trophy along the walk from Assembly Hall to Memorial Stadium, signifying the success of years past followed a group searching for that in the present.

The 1979 Hoosiers returned to Bloomington and were in the stadium Saturday for the 40th anniversary of the Holiday Bowl victory, the first bowl win in program history. For some it was the first time seeing their teammates and coaches in decades. Many brought their wives, some brought their kids. They didn’t all recognize everyone. They joked about their AARP cards. But they were together.

“40 years later, the light of this team shines bright as ever,” Mark Deal, IU's Assistant Athletic Director for Alumni Relations, said to the crowd at the dinner. “That light of this team will shine forever. What we did, nobody can take away from us. It will outlive us all.”

***

They called themselves the “Corso Men.”

It was the nickname given to the players on the 1979 IU team, the players under head coach Lee Corso.

They were the ones who saw Corso on the gridiron, and not behind a desk on ESPN. They knew the energetic and quirky coach long before America did.

“The thing about my father is people watch television now, on ESPN, and they think, ‘Wow, how fun is that guy,’” Steve Corso said. “But he was a coach before he was television person. The things he brought to coaching were inventive and fantastic and wild. This thing at ESPN is great, he loves it. As a coach he was entertaining to his own players day after day after day. We would show up and want to hear from our coach. You never knew what he would say or do.”

***

As summer 1979 turned to fall in Bloomington, Corso knew he had something building, the players knew it too.

But outside the locker room that wasn’t clear. IU hadn’t had a winning season since 1968. It had won just five total games in Corso’s first three seasons.

“Corso was great at selling the program and selling the idea that this program was building,” IU football and basketball radio broadcaster Don Fischer said. “You can imagine going into season number six and not having a winning season at that point, a lot of people just weren’t buying it.”

Halfway into the first game of the season, it looked to be much ado about nothing yet again, as IU trailed 26-3 at halftime on the road against Iowa.

But in that pink-painted visitors’ locker room with nails on the wall in place of lockers, something flipped.

“Coach Corso was pretty intense,” offensive line coach Harold Mauro said. “Really the catalyst that I think for that game when we were at Iowa, we were getting plummeted, we run a wheel route to Lonnie Johnson. He catches the ball, and I said, 'Oh please don’t drop it,' because there was nobody around. He caught it and ran it in.”

IU came back. It scored 27 unanswered points to leave Iowa City with a 30-26 win. It was the start of the special season Corso had described.

IU started 3-0, adding wins over Vanderbilt and Kentucky after the comeback over Iowa. It lost by one to Colorado before beating Wisconsin 3-0 on the road the following week, all before losing 47-6 to an Ohio State team that went 11-0 in the regular season and lost by one in the Rose Bowl.

The Corso Men bounced back with a 30-0 win over Northwestern before traveling to Ann Arbor to face Michigan.

“They literally had the game taken out of their hands by the officials,” Fischer said of the Michigan game. “I say that, and it sounds like sour grapes, but it’s the truth.”

In the final minute, IU scored and made the extra point to tie the game, the sleeve of Fischer’s sport coat catching on fire amidst the celebration as ash from his cigarette landed in a crease.

The Corso Men just had to get a stop. Michigan had only one timeout when it got the ball back with nearly 45 seconds remaining.

Michigan used the timeout early on in the drive and the clock drew closer and closer to 0:00 as Michigan moved toward midfield.

With 15 seconds left Michigan’s running back received a pitch out toward the sideline, but he realized he wouldn’t make it to the sideline and stop the clock. As he was brought down, he threw the ball to the sidelines. In fact, he threw it right to Lee Corso.

But instead of a being ruled an illegal forward pass, a penalty which would have ended the game, it was ruled a fumble. The clock was stopped, and Michigan gifted one more chance.

The Wolverines took advantage.

With six seconds left Michigan found Anthony Carter for a 45-yard touchdown, IU’s two defensive backs covering Carter running into each other. The Michigan players and students rushed the field.

“It was the most heartbreaking loss that I think I’ve ever seen,” Fischer said.

IU dropped to 5-3 after the loss. But it was one win away from the winning season that had eluded the program for so long.

The next week, Corso got a sixth win as IU beat Minnesota 42-24, and added a seventh with a 45-14 win over Illinois. Suddenly IU was 7-3 heading into the Old Oaken Bucket game.

At the reunion dinner, Deal gave out cards with a team photo on the front and “What have you done to beat Purdue today?” written across the bottom in red.

On that November 1979 day, IU didn’t do enough to beat Purdue. The Old Oaken Bucket stayed in West Lafayette and IU dropped to 7-4.

G.E. “Vinnie” Vinson walked into IU’s locker room following the loss to Purdue. Vinson was the president of the Holiday Bowl. He invited the Hoosiers — still comprehending and recovering from a loss to Purdue, the biggest game of the season — to play.

“There weren’t 40 something bowl games back then,” Tallen said. “That was an honor to be playing that game.”

For the first time since the Rose Bowl in 1967, and the second time in 75 years, IU was going to a bowl game.

***

“When we landed in San Diego for the Holiday Bowl, my father gathered the team on the tarmac and he said, ‘Indiana, this is the second bowl in 75 years we’ve been to,’” Steve Corso said. “He said, ‘We are going to have fun. You deserve it.’ He said, ‘The first rule, no curfew. Second rule, change your shirt in the morning so it’s not so obvious you’ve been out all night.’”

The pressure wasn’t on IU, it was all squarely on the side of its opponent, undefeated and top 10-ranked BYU.

“It was obvious who they thought was going to win from day one, and we took that to heart,” Clifford said.

National belief was that IU didn’t belong on the same field as BYU. So that’s what Lee Corso told the media. Or at least that’s what it looked like on the surface.

“My father says at the beginning of the week out in public, ‘I’m going to lull these guys to sleep, and then we’re going to beat their ass,’” Steve Corso said. “He goes to all the events and he says, ‘Oh we’re so lucky to be here. They’re the seventh best team in the country, we’re just happy to be here. Thank you for inviting us. We’re stepchildren.’”

IU practiced in shorts and wore shoulder pads just once all week. The IU players spent time at the beach while BYU practiced twice a day, with pads. IU was trying to give off the impression of handing the trophy to BYU.

“My emphasis there was that they had almost nothing to lose, to just relax,” team sport psychologist Scott Greer, nicknamed ‘The Guru’ said.

They took the field in San Diego with red helmets, a white stripe down the center and a white capital “I” on the side, white jerseys with red numbers and red pants.

With a week of light practice and sun, IU was loose and relaxed. Greer had emphasized there being no pressure, and he was right. But they were focused.

BYU was focused too, but they were tense, scared to make a mistake against a team they believed to be inferior. IU’s players only needed to see the demeanor on the BYU sideline that night to know they could win.

“On that night we could have played for seven hours and they wouldn’t have beat us,” Steve Corso said.

IU hung with the deemed superior group. BYU had far more total yards in the game, but IU played keep away, holding the ball for as long as possible. As the fourth quarter began, IU trailed just 34-31.

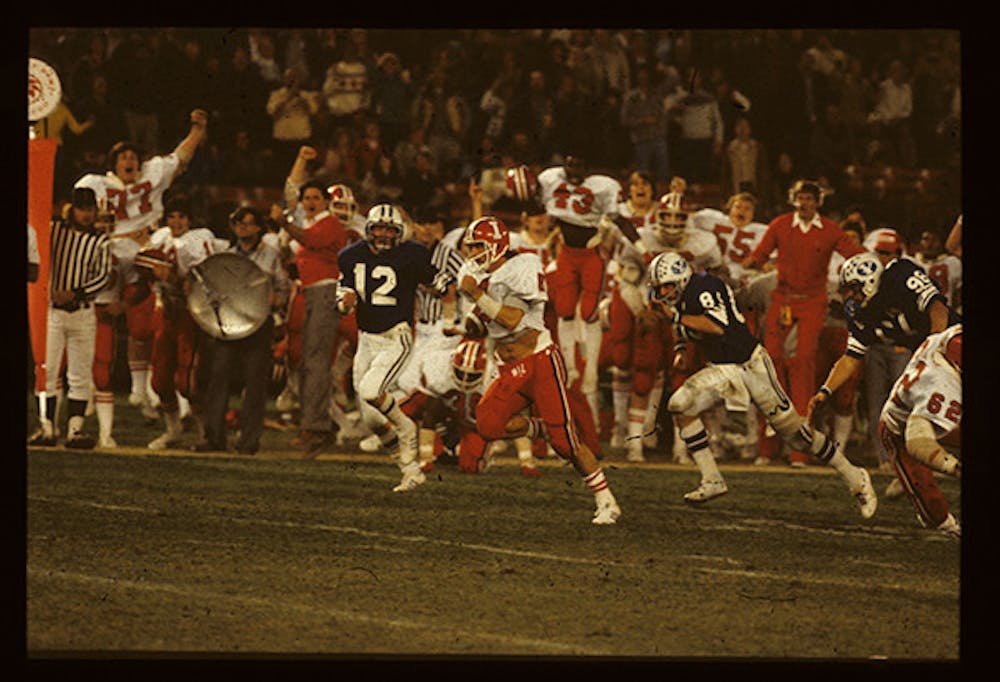

The lead was up to 37-31 as BYU punted to Tim Wilbur.

It was a short punt landing near midfield as Wilbur was called to back away. The ball bounced and bounced off Wilbur’s teammate, Craig Walls. The ball bounced off the ground again and kicked up, right into Wilbur’s arms at his own 38-yard line. He picked it up right in stride.

Wilbur found a crease on the sideline and ran behind blockers. After passing the BYU 40-yard line he cut back toward the middle of the field, dropping a BYU defender. At the 15, he broke one final tackle, and he was in the clear.

Wilbur raised the football in the air as he crossed the goal line. IU led 38-34.

“Everybody called me slow,” Wilbur said. “I always tell them I never got caught from behind.”

There was still time left, and just like in Ann Arbor, IU’s defense had to get one final stop to hold on against a top-10 team.

Quarterback Marc Wilson and BYU marched toward the end zone on the final drive, ultimately lining up for a 27 yard field goal. Lee Corso called a timeout to ice the kicker, a somewhat new concept at the time.

During the timeout, Lee Corso turned to Father James Higgins, who traveled with the team.

Father Higgins moved to Bloomington in 1967 where he founded and directed the St. Paul Catholic Center of Indiana University, working there until 1983.

He was on the sideline with the Hoosiers in San Diego. He and Corso were kneeled on the ground next to each other as BYU lined up for the kick.

“It’s a million Mormons against one Catholic priest,” Lee Corso said.

“Don’t worry about it, I got it,” Father Higgins responded.

Bill Doba coached the field goal blocking unit. That group was facing one of the nation’s best kickers, Brent Johnson. Doba called an all-out blitz. He could see Johnson looked out-of-sorts, the same nervous energy that had loomed over the BYU sideline all night. Doba’s own kicker Kevin Kellogg, saw the same thing.

Doba said the kick didn’t get more than eight feet off the ground before it started hooking right into the stands. As the kick sailed wide, Doba turned back to Kellogg.

“Kickers know kickers,” Kellogg said.

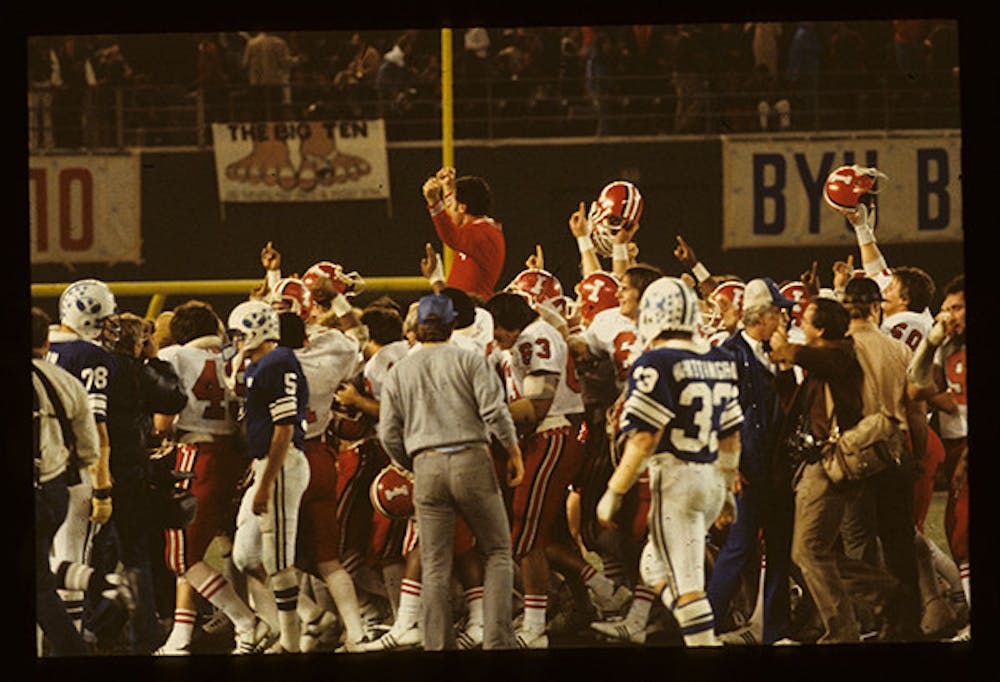

The IU sideline stormed onto the field, despite there still being just a few seconds on the clock.

Clifford took a knee and the clock expired, he thrust his arms in the air turned toward the crowd behind the end zone. IU stormed the field again. They didn’t have to come back that time.

“Thank god!” Lee Corso said.

Father Higgins responded, “You’re welcome.”

***

Forty years later the Corso Men watched the highlights on a projector screen in the front of the Henke Hall of Champions. The then-quiet Memorial Stadium in the aftermath of that afternoon’s game rested just beyond the screen.

They erupted with cheers as they watched Wilbur return the punt against BYU, just as they did 40 years before on the sidelines.

The legacy of the 1979 team is already cemented. Gifts like the donation from Tallen to build the Terry Tallen Football Complex, a new locker room and facility to rival that of nation’s top football programs, just extend that legacy further.

Inspired from his days recruiting while playing at IU, it’s a complex Tallen believes will help IU, which has already landed the top two recruiting classes in program history in consecutive years, to recruit at an even higher level.

And the teammates want the legacy to stretch further into the facility bearing their captain’s name.

The 1979 Hoosiers launched two “Legacy Locker Campaigns” at the reunion dinner, both hoping to raise $10,000.

The first campaign is to name a locker in honor of the Holiday Bowl champion team. The intended plaque will read: “1979 Holiday Bowl Champions, IU’s First Bowl Championship”.

The second is to name a locker in honor of Lee Corso. “The Men of Corso, 1973-1982, In Honor of Coach Lee Corso and His Coaching Staff” the plaque will read.

Lee Corso wasn’t there with his team that Saturday night. ESPN duties kept him in Austin, Texas. But his men watched a video Corso made for the night, seated at the College Gameday desk.

“The good news, I’m still working, 84 and still at it,” he said. “I miss and love you all very, very much.”

They missed him too, and they’re planning him an 85th birthday party.

The lockers will be the symbol of the past success in the midst of the Hoosiers trying to close the gap with the top of the Big Ten. The program’s moments of glory, no matter how fleeting or fast, will follow the team, even if not quite as literally as Clifford carrying the trophy behind head coach Tom Allen’s 2019 group.

Allen experienced that himself as he took the elevator up from the team room in the Memorial Stadium lower level following his postgame press conference to the third floor where the reunion dinner was being held.

He spoke to the Hoosiers of the past about the Hoosiers of today, a group searching to return to a bowl game just as that 1979 team did. He spoke about how he strives to win a bowl game, something just that 1979 team and two other teams in IU history have ever done.

As Allen left the dinner and shifted his focus to his next opponent, Ohio State, he had witnessed one of those moments of Hoosier football success that could be missed with the blink of an eye. He knows the expectations of the Corso Men lay on his shoulders, no matter how many years after Holiday Bowl have gone by.

The Corso Men all played at IU, but as Tallen said, there was no “I” in that team. Every speaker talked about that group as a family, that the players didn’t join fraternities because the football team was just that.

They weren’t the same athletes they were in 1979. They weren’t ready to take the field and face an undefeated BYU team. But one of the most successful teams in IU history was together once again. It didn’t matter how many gray hairs, or lack of hairs, the players and coaches had. Age can’t take away their glory.